BALLISTIC PARACHUTE RECOVERY SYSTEMS – THE BALLISTIC BACKUP PLAN THAT MIGHT SAVE YOUR LIFE

John Nixon was flying from Queensland to Dubbo, overlooking the Gilgandra district from 5000ft when he experienced any pilot’s worst nightmare. On that sunny November day in 2012, when everything seemed to be going smoothly, the Cirrus SR22-G3 he was flying suddenly lost oil pressure and the engine seized. Acting quickly, John set the plane to glide into Gilgandra airport, but soon realised he wasn’t going to make it. In a stroke of luck, John owned a plane exactly the same as the one he was flying that day and was familiar with the Ballistic Parachute Recovery System (BPRS) in that aircraft.

“I informed air traffic control about the emergency situation, turned the plane away from traffic on the Newell Highway and headed into a big open paddock,” said John. “Not many people in the world have set off an aircraft emergency parachute, but I had attended a training course at Wagga Wagga about 18 months [earlier] and knew exactly what to do. We were on the ground less than a minute after the oil gauge indicated the problem.” In this instance, John and his passenger Tom were extremely lucky their aircraft had a BPRS fitted. With a rising number of these lifesaving devices being fitted to aircraft across Australia, BPRS are growing in popularity and John and Tom have the system to thank for saving their lives. As any experienced flyer would know, safety is paramount – so how exactly do these systems work and are they worth the investment?

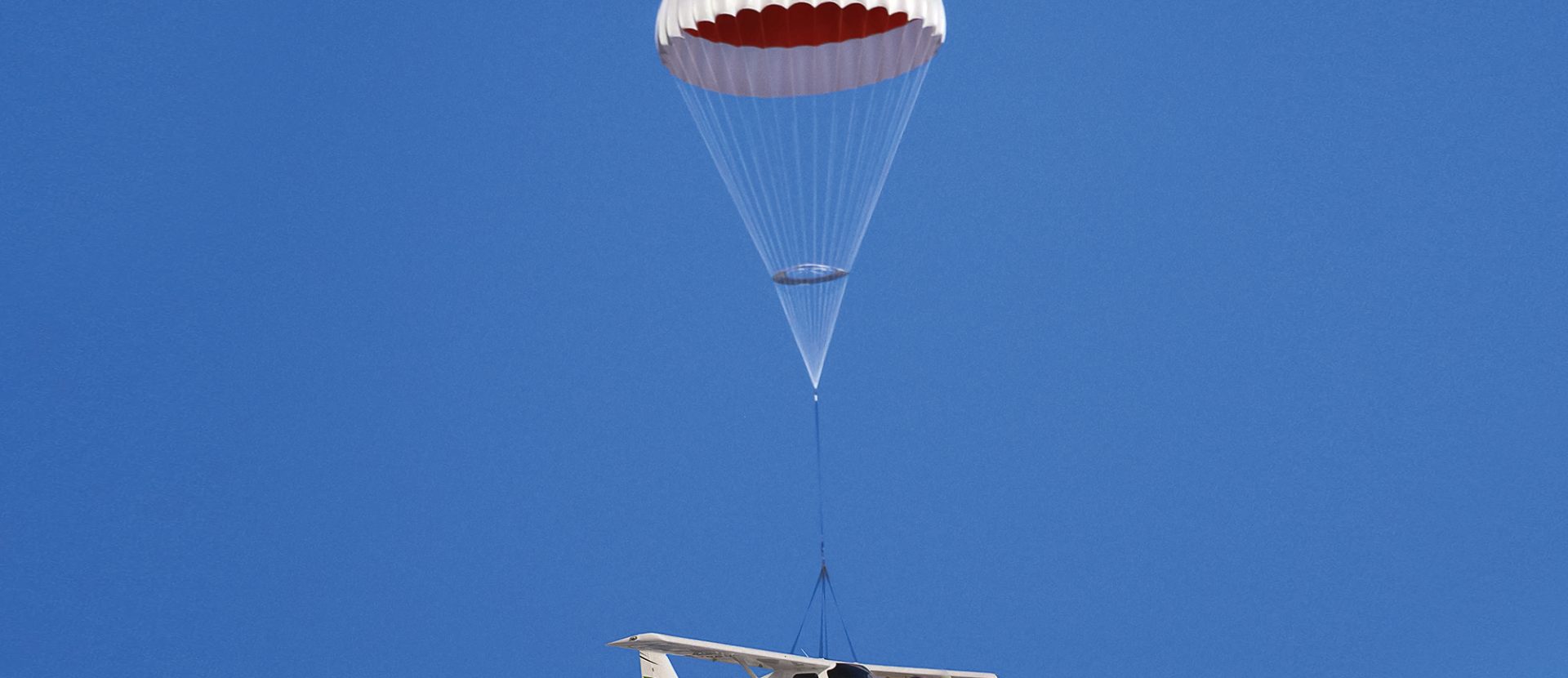

Boris Popov, the founder of leading manufacturer BRS Aerospace, developed the first Whole Aircraft Rescue Parachute System (WARPS) in 1980 and since then, BRS systems have been installed in over 35,000 aircraft worldwide. In case of an emergency, the deployment handle of the system is pulled, the attached rocket fires and the chute is extracted. An equipped speed-sensing slider controls how fast the chute opens and the parachute then inflates, resulting in the aircraft being gradually lowered to the ground. BPRS are designed to be used when the chance of survival is otherwise low, usually due to a loss of control. This may be caused by catastrophic in-flight structural failure, control system failure or jam, failed spin recovery, disorientation in instrument meteorological conditions, pilot incapacitation or midair collision. According to BRS Aerospace, an aircraft will still likely suffer some significant damage and the terrain of the landing will greatly affect this. BRS Aerospace claims that most general aviation aircraft that have come down under a BPRS deployment have eventually flown again. So, not only do these systems have the potential to save our lives, but they may also avoid a total write-off of the aircraft.

However, deployment of the system does carry its own risks, and once the parachute has been deployed, the pilot has little control over the impact point of the aircraft. The descent rate under the parachute is also quite high and there is still a significant chance of injury upon landing. If you ask me though, a possible chance of injury is a better option than probable death.

Starting from $6,000 for small aircraft and reaching prices of up to $38,000, parachutes are available for aircraft weighing between 272 – 1,600kg. With prices and weight varying depending on each aircraft, a system added to a typical 600kg LSA aircraft would cost approximately $11,000 plus GST and add approximately 12kg of weight, according to Bryn Lockie from BRS Aerospace. While these devices aren’t necessarily cheap or super light, should worst come to worst, this may be a small price to pay to save not only your aircraft but also the lives of you and your passengers. In the end, it ultimately comes down to a question of how much you’re willing to pay for that extra backup plan when all else fails. According to BRS Aerospace, a total of 448 lives have been saved by their parachutes at the time of this writing – so what price can we put on our own lives?

The lifespan of any product is always another important consideration and you may well be wondering what we can expect from such an investment. Systems for certified aircraft have a 20-year lifespan, but as with most aircraft equipment, WARPS require maintenance. BRS Aerospace advises that for certified aircraft, the chute needs to be repacked every 10 years as well as the rocket replaced. Also, a small mil spec line cutter must be replaced every five years. Sport aircraft systems have a 25-year lifespan, and it is advised the chute be repacked every six years and the rocket replaced after 12 years. BRS Aerospace provides these services for a fee and customers are encouraged to ship their product back to the company for repacking. While these systems aren’t cheap, they have a long lifespan and one system should last you the better part of your flying career as long as it is well-maintained and serviced.

Further cementing their place as a viable safety option, certain aircraft manufacturers have embraced BPRS. The Cirrus Airframe Parachute System (CAPS) – a collaboration between BRS Aerospace and Cirrus – now comes fitted as standard equipment in the Cirrus SR20, SR22 and SF50. If it wasn’t for this collaboration and the fact that CAPS now comes as standard, John and Tom might not be alive today. “The Cirrus is a bloody good aircraft and everything went to plan,” said John, who escaped with only a few bruises while Tom was completely uninjured. Ultimately, these systems are a significant investment in terms of installation and maintenance costs, but the evidence of their effectiveness speaks for itself. Like John and Tom, a BPRS may just save your life in the event of an otherwise unavoidable worst-case scenario. You can never have too many backup plans when it comes to safety and a BPRS is a great option for that extra peace of mind.