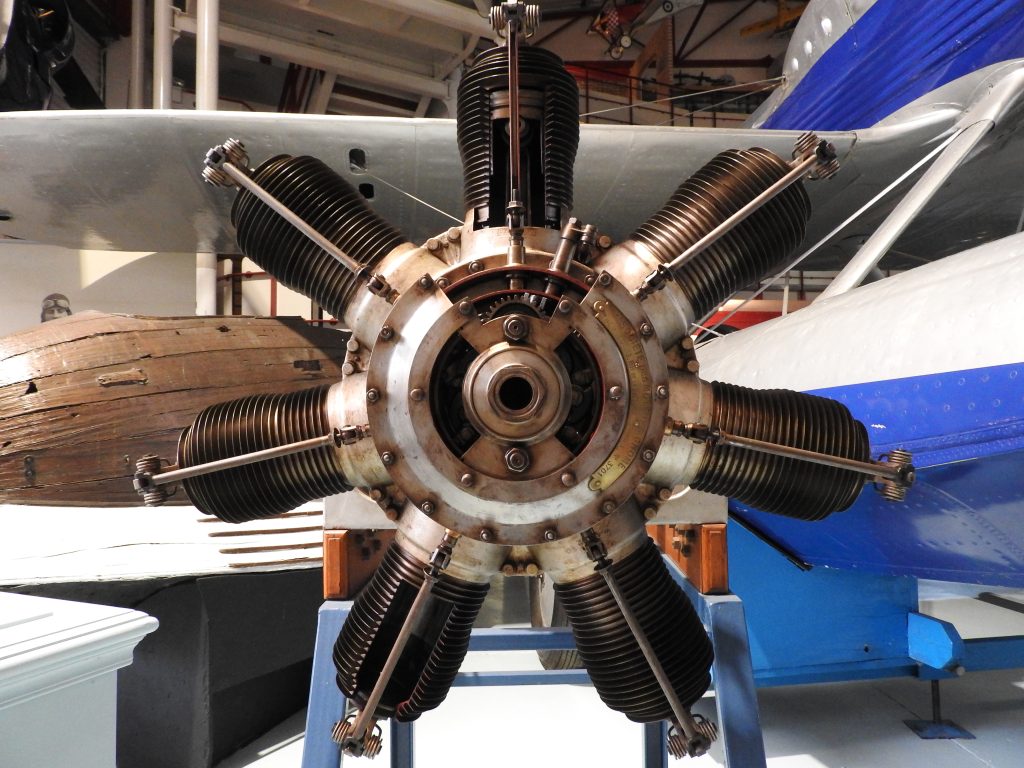

This is a photograph of what is considered one of the oldest surviving rotary engines — a fivecylinder design that powered a tricycle designed by Félix Millet and which dates from 1888. Early rotary engines were popular for their compact size and lightweight. Lighter, certainly, than the more “conventional” engines in existence at the time. For example, Millet’s rotary weighs only 13kg.

The lightweight nature of the rotary engine made it an enticing option for budding aircraft designers. In 1908, the Seguin brothers used this principle in their first aero engine — the 7-cylinder 50hp Gnome. Their first variant, the Omega, was a complex but fairly reliable valve-in-piston crown arrangement that required some constant fine tuning to work reliably. Mismanagement of the timing function could provoke the engine into catching fire, earning it the unfortunate moniker of the “Catherine Wheel”. They were also prone to shedding the occasional cylinder, but over 60 early aircraft types utilised this engine to great success.

Because it was far too complicated to devise a recirculating oil system with the whole engine rotating, it had to be a total loss system with a gear-driven oil pump delivering oil to the mains and big ends. Everything else was splash-lubricated. Oil entered the combustion chamber with the mixture and was ejected through the exhaust valve (which is open to atmosphere), and the spray from that kept the exposed rocker gear lubricated — as well as the airframe and pilot!

The further development of the 9-cylinder version generated about 65hp and was used extensively on military aircraft in the early part of WWI. Nonetheless, there continued to be two big problems: adjusting the inlet valve timing required the removal of the propeller and front plate, and it was also very twitchy. Trying to get all 9 cylinders set evenly was a complex procedure, but the biggest problem was that the valve quickly became coked up, causing it to jam open. The spark would then ignite the entire contents of the crankcase, either blowing the engine apart or setting fire to all the oil inside the cowling.

The rotary was the engine of choice throughout WWI because of its excellent power-to-weight ratio, (relatively) good reliability, and lack of susceptibility to action damage. They were even flown home with one cylinder shot off, although the developing vibration must have been rather disconcerting! Because there are no reciprocating parts, they are relatively smooth, unlike inline engines.

The Omega’s valve-in-piston arrangement was bound to be improved, and this was achieved with the 7-cylinder Type A, which was the first monospace (single valve) design. This brought a new level of simplicity and reliability to the 7-cylinder concept that quickly developed into a 9-cylinder arrangement. This 9-cylinder variant became one of the most widely used engines of WWI.

Rated at 80hp, the 7-cylinder Type A only had a brief period of popularity, powering early variants of the Avro 504, the Avro 511, a Bristol-Coanda monoplane and the Sopwith Pup, as the more powerful 9-cylinder version became the preferred option by manufacturers. There was also a brief flirtation with what we would now describe as Variable Valve Timing which can be spotted on the Type A on display at the Solent Sky Museum, Southampton. Engine speed could be controlled by varying the opening time and extent of the exhaust valves using levers acting on the valve tappet rollers, but this was not successful and was later abandoned due to engines overheating and a scorching of the valves. Amongst the range of rotary engines used during the War, the biggest ever built and used was the 200hp Bentley BR2. Anything bigger became hampered by the large windage losses caused by rotation, difficulty in breathing, and the very large Coriolis forces which affected the handling characteristics of the aircraft they were fitted to.

Most World War I enthusiasts, especially those who are constructing and flying veteran aircraft, are aware of the New Zealand-based Classic Aero Machining Service’s 9-cylinder Gnome monospace rotary engine — the 9B — and its success in powering some of the more authentic reproductions around the world today. The modern 9B, developed by CAMS owner and chief engineer Tony Wytenburg, is a masterpiece of analytical improvement on the original type, which delivered around 100hp. Today, with some very tiny modifications to the shape of the aspiration vents around the base of each cylinder, Tony’s engines deliver a little over 120hp and can be taxied extensively without “oiling up” as the originals were prone to do. They also start reliably and they do not rich-cut like other rotary engines can do. They’re simple and easy to operate.

With Tony’s 9-cylinder Gnomes enjoying success today, I believe there is a gap in the market for an engine with a little less power whilst still retaining some authenticity in the way only a rotary feels in flight, not only for the constructor market but for museums that fly early types that are wondering just how long their original engines will last. With this intent, I am working with CAMS on the development of a Type A prototype (#701) with the belief that our small community needs this option available for the future.

The CAMS Gnome 7 Type A is expected to be a little over 90hp, based on the developmental experience of the 9B. Its appearance is authentic to the original, with improved strength around the base of the cylinders and, of course, it can be used in both tractor and pusher variants. The prototype 7A is scheduled to be seen at the Classic Fighter Omaka Air Show in New Zealand Easter 2025.