HOW IMPORTANT IS RADIO IN A MODERN AIRCRAFT? NICHOLAS HEATH FINDS OUT.

When I learnt to fly, the mantra was always ‘aviate, navigate, communicate’ in that order of priority. And let me tell you, there was a long drop-off after aviate and plenty of daylight between navigate and communicate. Radio communication was deemed desirable but not fundamental to flying. So, what has changed since then?

Well, the first noticeable change is in the quality and price of radio equipment. In the planes I used to fly around with my father in the 1970s – mostly Cessna 182s – you had a King radio with a speaker over your head and a microphone on a twisty cord. That was it. Headphones were for the professionals.

Fast forward to now and we have noise cancelling headphones with Bluetooth connection to our phones. Things have really changed. Perhaps the not-so-obvious change is the availability of high-quality radio sets for a lot less money than before. You can buy a Funke ZATR833S transceiver that fits in a standard 2¼-inch instrument hole and puts out 6 watts of power for a little under $1900 AUD.

I recently bought an Icom IC-A25NE, a handheld portable (think walkie-talkie) that includes GPS and VOR plus Bluetooth for under $700 AUD. I bought it as a back-up and for coordinating ground ops, but if you add a simple headset like a Pilot PA51 for around $200, you have a full Navicom set up with more capabilities than we ever dreamed of back in the 70s for under $1000. It’s just as well, because radio communications have grown in importance.

The most obvious change in communications is around the circuit. Different pilots interpret the requirements and there’s a lot more being said. Of course, all this extra calling has led to a much more crowded airwave. Probably the most frustrating thing on the radio is some people having a good old chat about conditions or the price of fish when you’re trying to make or hear a call. Don’t get me started.

According to the Civil Aviation Advisory Publication CAAP 166-01, the correct format for a radio call is

- Location Traffic – Aircraft Type – Call Sign – Position/Level/Intentions – Location

That translates in real life to: “Parkes Traffic, Tecnam 4692, One-zero miles north inbound on descent through 4,200, estimating circuit at three six, Parkes” That call should take a bit less than 10 seconds. Any faster and it’s a jumble. Any slower and you’re taking up valuable frequency space. The commercial traffic speak at rates that us humble amateurs can’t hope to replicate. When I fly in controlled airspace, I find the speed and depth of communication to be a big jump on what I’m used to. When dealing with ATC, between deciphering the communication, understanding what has been said and then reading it back to them, I’ve found it can be a challenge if you don’t do it often. If there are two pilots in my plane – and there usually are if I’m going into controlled airspace – then one will fly while the other works the radio and nav. That’s how the commercial traffic do it and I can see why. It’s a lot to do while trying to fly an aircraft.

The current debate over expanding Class E airspace – which requires a transponder – makes it likely that in the future, more RAAus aircraft will have a transponder fitted. Currently, roughly a third of aircraft have them. So why do we need a transponder and more importantly, why in Class E Airspace? A transponder is very useful to air traffic control when identifying aircraft. While you are buzzing around with it set to 1200, it’s talking to secondary radar and giving ATC your pressure height. By having you ‘squawk’ a particular frequency, they can then use this to identify you on their screens from other traffic. It also provides a useful tool in a crisis with codes for emergency (7700) loss of radio (7600) and even hijacking (7500). I’ve often wanted some codes for lesser emergencies like ‘I really need to pee’ and ‘my pen fell under the seat’, but they aren’t on the list.

An important thing my first instructor taught me was to switch to standby when changing channels or at least be very careful when doing so. Here’s why. Let’s say you are stooging along with your transponder set to 1200 and ATC asks you to squawk 7421. So, you wind the left-hand knob down the dial to 7, then the second knob down to 4 and in doing so, you have just passed through 7700, 7600 and 7500. Yes, all the emergency channels. That’s not going to make you popular.

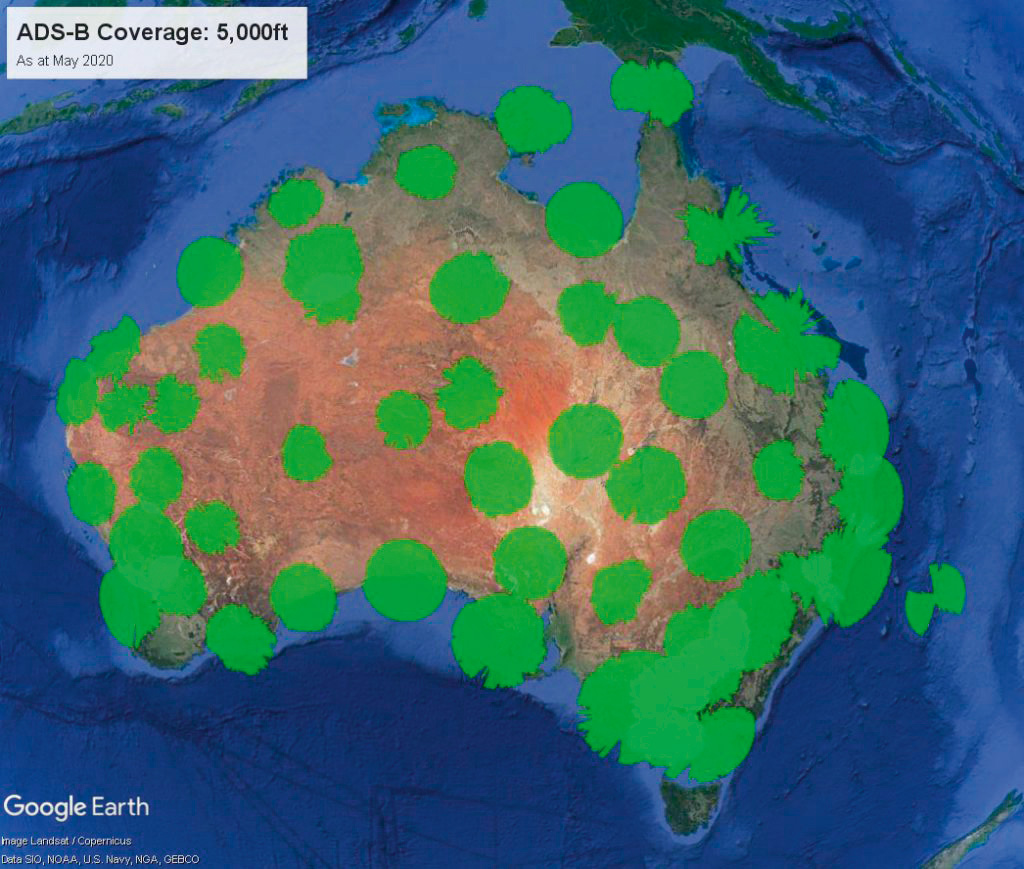

As if the radio stack wasn’t big enough already, the latest kid on the block is ADS-B, or Automatic Dependent Surveillance Broadcast. This is a clever piece of technology which transmits your position and other important information. That part is called ADS-B OUT. Seems kind of obvious. They call the other mode, ADS-B IN. I wonder how long that meeting took? The unit transmits your ID, your position, height, speed and direction, including vertical speeds.

So, a ground station has picked up your position and fed it in to the system. Here’s where the magic happens. Your aircraft can now pick up the data from other aircraft via ADSB-IN and you can see them on your nav or at least get a proximity warning. In the USA, ADS-B has been a mandatory fitting to all aircraft since 2020 operating in controlled airspace, but it hasn’t happened in Australia yet, unless you are flying IFR. So why is it mandatory in the USA for VFR aircraft in certain airspaces? It’s because of the high levels of traffic and the potential interaction of small, slow-moving GA traffic with large, fast-moving commercial passenger services. Which brings us nicely back to why in Australia a radio, transponder and ADS-B are more important than ever: traffic. A lot of people talk about the demise of aviation, but the fact is, despite the obvious impact of COVID-19, aviation has grown rapidly and there are more and more aircraft in the airspace than ever before.

The good news is that there are some affordable options – but with limitations. The SkyEcho 2 is a portable ADS-B IN/OUT unit accepted by CASA for under $900 with a 12-hour battery. This small unit has a range of about 40NM. That means you’re flying in a bubble with a diameter of 80NM, where you will see any other ADS-B OUT equipped aircraft. It connects to things like your tablet to display nearby traffic. I don’t know about you, but that makes me feel more comfortable to know who is out there – provided they have ADS-B OUT fitted. I know a lot of pilots who will say that they didn’t need ADS-B before, followed by a rant. It will be similar to transition from paper maps to GPS. It doesn’t solve everything. Most commercial traffic uses the TCAS traffic collision avoidance system which doesn’t talk to ADS-B. TCAS only talks to a transponder.

AN INTERESTING CHAT

Some days the radio chatter is more interesting than others. It’s a clear day in late 2005 and the perfect chance to freshen up some skills before my navigation exam.

I’ve grabbed my trusty steed, a Cessna 172 as old as me, which I liked to fly slightly starboard wing down. We head out of Geelong Airport for an anti-clockwise lap of the Bellarine Peninsula along the coast. There’s a stiff northerly, but it shouldn’t be a problem. I head south to Anglesea and then make a left tracking coastal for Port Phillip Heads. It’s a nice day with a fair amount of traffic about, meaning a lot of radio chatter. The beaches are packed because it’s hot. The parachutists are up and dropping over Torquay Airport.

As I approach Barwon Heads, I pick up a call on the radio, “… engine failure over Torquay, one POB…”. Now that is going to get your heart racing! I looked over my shoulder, I was about 5 miles from where they were. I couldn’t see anything. The base responded and told them to go to the company channel. So, they went off the air. As a student pilot, I wasn’t sure what to do. I stayed on course and switched over to what I knew was the local operating channel to listen in. I wasn’t sure if I could help or not. The pilot sounded a bit flustered, but I guess you would be.

The ground operator was trying to diagnose the problem. The engine briefly flared again, then died and the pilot reported he was ditching. Ditching? He had been over the airport a minute ago. At this point, I realised I probably should get back to the area frequency. I clicked over to hear my own base calling for me and sounding kind of desperate. Turns out they had heard a Cessna 172 in the area I was in was going down and they wanted to know if it was me! I quickly responded with a position and status.

A slightly shirty flight school operator let me know they expected a prompt response in the future. My bad. Suitably chastised, I headed on towards Queenscliff, but my heart was no longer in the flight and I cut short back to Geelong. Meanwhile the other 172, which had been carrying parachutists, had ditched just off White’s Beach in Torquay into shallow water. Thankfully, the pilot was fine. He’d got the parachutists out over the field when the engine failed.

Later that day, a tractor tried to pull the aircraft out of the water and succeeded in pulling the engine off the front of the aircraft. It kind of makes it hard to diagnose the issue after that. I’m still not sure how he had an engine failure over the field at 10,000 feet and somehow managed to end up in the water a couple of miles away. Like I said, that northerly was blowing hard. I took a few lessons from this. Listen up to the radio. You never know when the mundane will become an emergency and you might unknowingly be right in the middle of it. Secondly, if it goes down, let people in the area know you are there and what you are doing, provided you are not blocking the channel being used to coordinate the emergency. As a slightly more experienced pilot now, I would offer to assist if required, dependent on the nature of the emergency. But the best thing you can do is stay off the frequency and let them sort it out.

You will still need a transponder for Class E airspace. And, of course, you’ll still need to keep a proper watch, but that nagging feeling about a mid-air collision might ease a bit. There’s still a few more pieces of radio equipment you might come across.

On aircraft that fly in remote areas, you’ll often find a HF radio, a high powered, low frequency radio that has tremendous range. It looks like a normal radio however I recommend staying away from the antenna, it can give you a mighty kick with up to 200 watts of transmitting power. The other radio device you might see is a VOR navigation unit, a system that tracks ground-based radio beacons. Not that long ago, it was a very important piece of navigation equipment, however the induction of GPS has largely relegated it and ground-based beacons are diminishing in number.

So, what does all this mean? It means two clear things to remember for the future. Firstly, as traffic increases, we need to be better with our communication. Secondly, we are about to undergo a similar quantum change, such as the GPS revolution, but this time it is in how our aircraft talk to each other and ground stations. Got an opinion on the changes? Let us know at editor@sportpilot.net.au