REVISITING THE BASICS OF CAUSE, PREVENTION AND RECOVERY

On June 1st 2009, Air France Flight 447 took off on a long-haul flight from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, to Paris, France. 3 hours and 40 minutes into the flight, the aircraft encountered severe weather conditions with ice crystal formation in thunderstorms. This resulted in the aircraft’s pitot tubes becoming obstructed, leading to a temporary loss of airspeed data.

A lack of clear communication and coordination among the cockpit crew ensued, and a series of incorrect control inputs exacerbated the situation. This loss of accurate airspeed information caused the aircraft’s autopilot and autothrust systems to disconnect, leaving the aircraft in manual control.

At 38,000 feet Air France Flight 447 entered a highaltitude stall.

In the realm of aviation, the term “stall” carries a weight of seriousness that sends shivers down the spine of pilots and passengers alike. Often associated with catastrophic crashes, stalls are a critical and often misunderstood phenomenon. In this article, we will explore what stalls are, why they happen, and how pilots are trained to deal with them. We’ll also look at the stall’s bigger, scarier brother; the spin. We’ll discuss its causes and recovery methods.

STALLS

What Is a Stall?

A stall occurs when an aircraft’s wing loses its liftproducing capacity due to the wing exceeding the critical angle of attack. In simple terms, it’s when the wing fails to generate enough lift to keep the plane airborne. Contrary to what many outside the aviation community might believe, a stall doesn’t involve the engine cutting out or the plane suddenly falling from the sky. Instead, it’s a loss of control that can lead to dangerous situations if not handled correctly. A stall is, most times, a manageable event that can be recovered from with the correct processes.

The Aerodynamics Behind a Stall

To comprehend a plane stall, one must delve into the basics of aerodynamics. Aircraft wings generate lift when air flows over and under them, creating a pressure difference that keeps the plane aloft. As a pilot increases the plane’s angle of attack, the airflow over the wings becomes disrupted. If the angle of attack exceeds the critical angle, the wings can no longer generate enough lift to support the aircraft’s weight.

The Warning Signs

Recognising the early warning signs of a stall is essential to preventing it. Common indicators include a sudden loss of altitude, increased rate of descent on the VSI, and – if equipped – a distinctive audible warning from the plane’s stall warning system. Furthermore, the control surfaces may become sluggish, making it challenging to maintain the plane’s orientation.

Types of Stalls

There are three categories of stall; configuration stalls, maneuver-related stalls and power-related stalls. For this article, we’ll look at the two subtypes of powerrelated stall.

- Power-On Stall: This type occurs during take-off or climb when the engine is producing power, and the angle of attack becomes too high. It’s a situation where the pilot pulls the yoke or stick back too aggressively, leading to a stall.

- Power-Off Stall: This type of stall takes place when the power is reduced, such as during landing or during practice for a landing. A power-off stall can occur when a pilot doesn’t manage the descent properly.

Recovering from a Stall

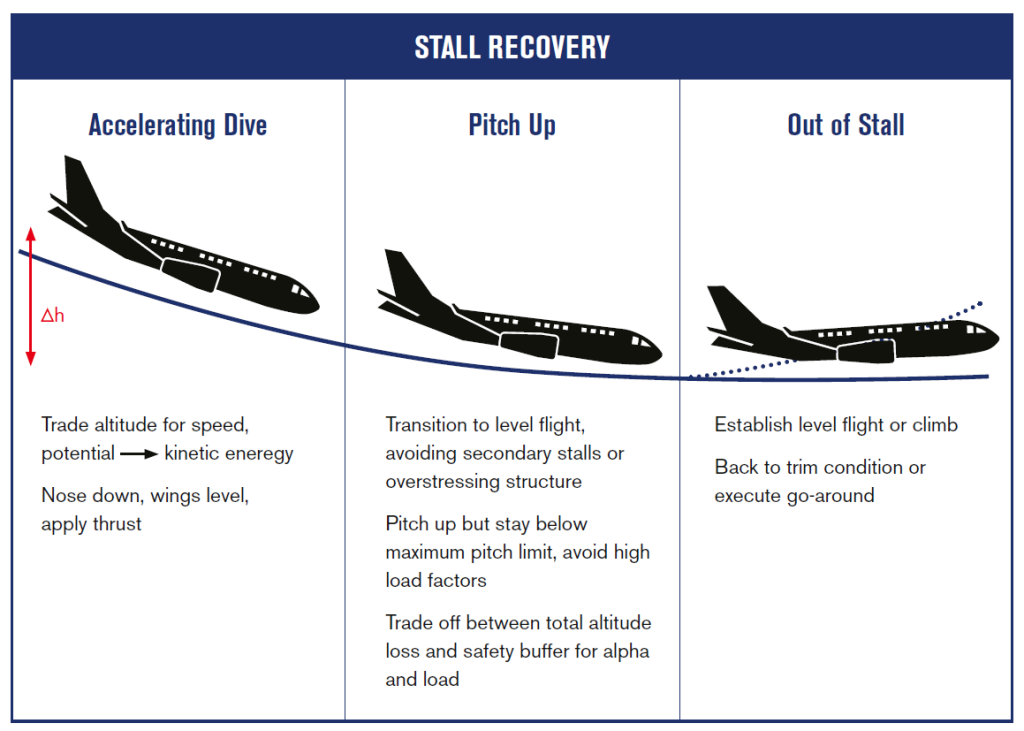

The key to surviving a stall is knowing how to recover from it. The fundamental procedure is straightforward:

- Reduce the Angle of Attack: To regain lift, the pilot must decrease the angle of attack by gently pushing the control stick or yoke forward.

- Apply Full Throttle (if power-off stall): If the stall occurs during landing or low-power settings, applying full throttle can help the aircraft regain airspeed and climb.

- Level the Wings: The pilot should level the wings to prevent an uncontrolled roll or spin.

- Climb: Once the plane has recovered from the stall, the pilot should establish a positive rate of climb to regain altitude.

- Assess the Situation: After recovering from the stall, it’s crucial to assess the situation, address any altitude loss, and continue the flight safely.

SPINS

Spins are one of the most feared aerodynamic phenomena in aviation. Often depicted as dramatic spirals to certain doom, the reality of a spin is far more manageable with the right knowledge and training.

What is a Spin in Aviation?

In aviation, a spin is a specific type of uncontrolled descent where an aircraft no longer produces sufficient lift to maintain height, and rotates around all three axes (pitch, roll and yaw) at varying degrees. During a spin, the aircraft will rapidly descend in a vertical path. A spin can be highly disorienting and, if not promptly recovered, can lead to a loss of control and, in extreme cases, a crash.

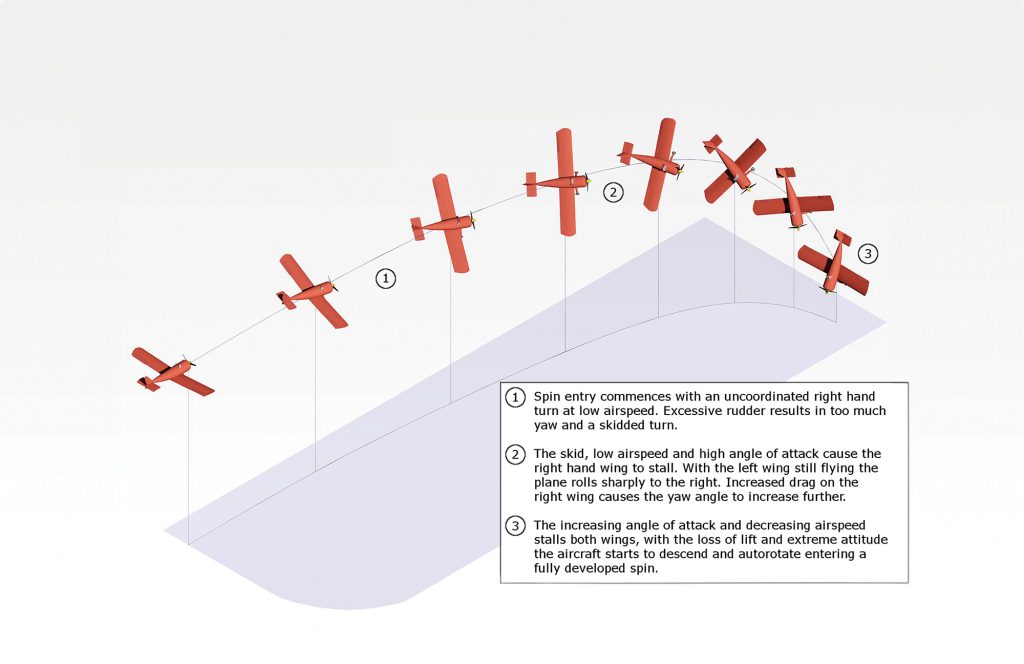

Conditions Leading to a Spin

A spin can occur when a number of factors come into play. Firstly, the start of autorotation is initially brought on by an asymmetric stall, that is, one wing has stalled first or deeper than the other. Lack of recognition of yaw and balance is ultimately where the spin starts and can rapidly develop. Other contributing factors are us; the human. We often react negatively when startled by the realization of a developing spin, only making the situation worse. Unfortunately, this often happens in phases of flight where we are not ready for it are unable to recover such as take-off, landing or low-level maneuvering where angle of attack awareness is compromised.

Recovering from a Spin

Recovering from a spin is a critical skill for pilots, and the process can be quite different depending on the aircraft type. Here are the general steps for recovering from a spin:

- Power Idle: Reduce the throttle to idle to eliminate any additional thrust that may be sustaining the spin.

- Ailerons Neutral: Ensure that the ailerons (control surfaces on the wings) are in a neutral position, as applying aileron input can exacerbate the spin.

- Rudder Opposite to the Spin Direction: Apply full opposite rudder (opposite to the direction of the spin) to stop the yaw rotation.

- Elevator Forward: Gently push the control stick or yoke forward to lower the aircraft’s nose, reducing the angle of attack and breaking the stall.

- Recovery: Once the rotation stops, and the descent is under control, recover to level flight by using coordinated control inputs.

Recovering from a spin requires training and practice, as it can be a disorienting and potentially frightening experience for a pilot.

Spin Prevention

The best way to manage spins is to prevent them from occurring in the first place. Pilots are trained to maintain coordinated flight by ensuring that their control inputs (rudder and ailerons) work together to keep the aircraft’s movement smooth. A lack of coordination, especially during slow flight or while manoeuvring at low speeds, can increase the risk of a spin.

Early in the morning on June 1st, 2009, Air France Flight 447 disappeared from radar. There was no distress call. All crew and passengers were assumed dead. It was not until almost two years later than the black box was finally recovered.

The black box revealed panic onboard amongst the pilots as the aircraft’s instruments became incapacitated. At 35,000 feet the pilot put the plane into an aggressive climb to escape the poor conditions. At 38,000 feet, the aircraft began to stall. No longer in control, the Airbus A330 began to fall at a rate of 10,000 feet per minute. All lives onboard were lost.

The crash of Air France Flight 447 highlighted the importance of pilot training, especially in managing unreliable airspeed situations, and the need for advancements in cockpit automation and pilot awareness. The recovery of the aircraft’s flight data recorders from the ocean floor helped investigators piece together the events leading up to the tragedy and provided valuable lessons for aviation safety.

We’ve only just scratched the surface of the information there is to know about stalls and spins. If you’re interested in learning more, check out the “Loss of Control” video series on the RAAus YouTube channel.