IS YOUR AIRCRAFT SAFELY TIED DOWN?

I know a lady who stressed so much that she had left the iron on at home, she now takes it to work with her. Not an elegant solution, but effective. Wondering about your aircraft parked on a field when the weather comes in is a similar worry. The recent season of wild weather has reminded many of us that securing your aircraft is something you need to take seriously.

Most of us have a good arrangement at our home base. It’s when you find yourself visiting elsewhere that you need a good, portable, lightweight and effective system. Here, we’re going to focus on your away plan, but most of what we discuss will apply to any for fixed wing, light aircraft, permanently tied down on the flight line.

First, let’s talk about why we tie an aircraft down. I know this seems obvious, but let’s look at the physics involved. Even the most STOL aircraft is going to need twenty-five plus knots of wind on the nose to generate enough lift to make the wings work. A tail dragger will have a greater angle of attack, so it might be at earlier risk. For a nose wheel aircraft, that wind speed will probably exceed the stall speed. So, it’s going to be a pretty significant wind event that flips an aircraft. Far more likely is that the aircraft starts to move horizontally. Then you have the risk of the aircraft colliding with infrastructure or, worse still, other aircraft. So first we secure it in position, then we stop it flying away.

Chocks away!

Your first defence against horizontal movement are chocks and a handbrake. The aircraft I regularly fly doesn’t have a handbrake. Recently, I landed on a very windy day and when I climbed out of the aircraft it proceeded to blow down the flight line. I had to fish around for my chocks, then jump out and throw them under a wheel. Picture a mature man of generous proportions, trying to get out of an aircraft quickly, then hold on to it against the wind while trying to position a set of chocks with his foot. Not elegant. Fortunately, I carry a set of nose chocks that I had made up by the simple expedient of cutting a 6”/15cm block of 4×2/100x50mm wood on the diagonal to for two chocks and joined them with a short piece of rope. Total cost, zip. I have now made up a set for all wheels.

I’d like them a little taller, but the wheel fairings make that hard. If you’ve got a park brake and the manual says you can leave it on, then that’s great. But I would always chock as well. Brakes can slip. Some aircraft don’t permit them to be left on. If you’re not feeling crafty, there’s a bunch of good chock options available commercially.

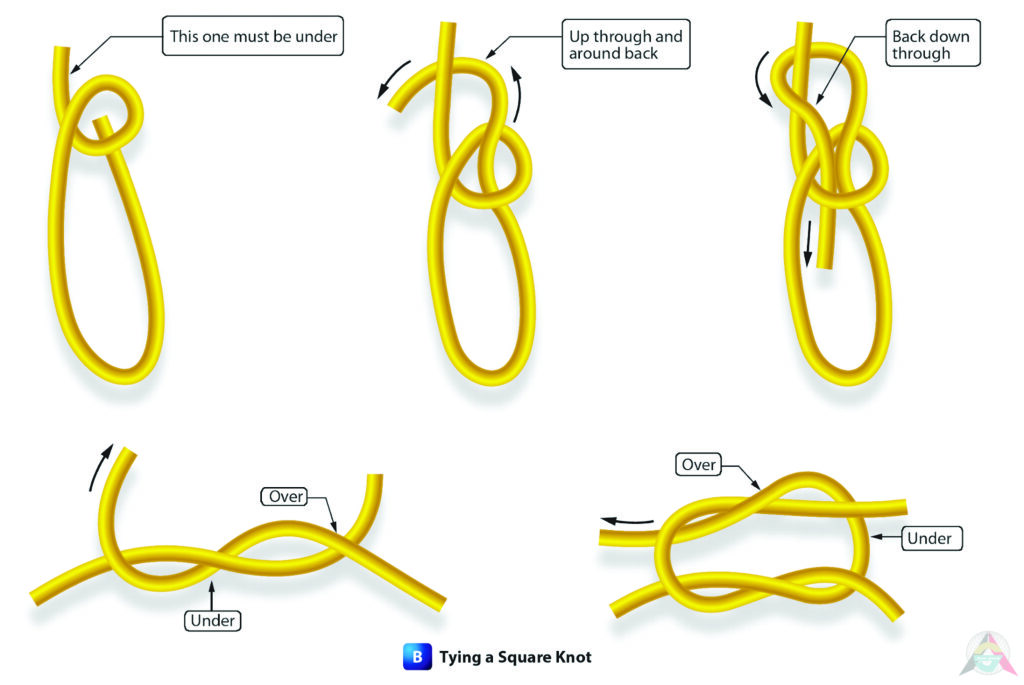

I use ropes, because I always have. I see a lot of people now are using ratchet straps. I’m not so sure about that. I like ropes with a bit of spring in them to act as a shock absorber. I don’t know if a ratchet strap will give that. I also worry that people are cranking them down, which can’t be good. I’d be pleased to hear your thoughts. I have invested in some carabiners so that I can easily connect one end. At the other end I use a bowline knot. As bit of a yachty, the bowline knot is preferred because it doesn’t matter how hard you pull the knot, it is easy to break out. I don’t like to tie down hard. I always leave a little bit of play.

The manual recommends 1 inch/2.5 cm – whatever that means. Too loose and the aircraft can bang. Too tight and you can put negative loads on that aren’t meant to be there. I definitely don’t want the aircraft banging against the harness, but I don’t want it cranked down either. I am starting to think that a rope or strap with it should go without saying that you would only ever use the tie down points on the aircraft. Never use a strut or control surface.

Against the Wind.

Blessed are the airport providers who install tie-down points, for they shall inherit good Karma. Or something like that. There’s nothing better than arriving at an airport and finding tie-down points in the GA parking area. Rings in the ground are good but they never seem to be in quite the right place. Those long cables work pretty well too. Unfortunately, many airports don’t have them; if they do, there’s no space. So, you’re on your own.

So, let’s imagine the scene. It’s a balmy afternoon and I’ve just arrived at Remotesville Regional Airport. There are two hangars, a wind sock and a toilet built by the Rotary Club. The ERSA will normally outline a parking spot. Maybe. I like to do the right thing and park in the designated area, even if there’s a lot of space at an airport. But, if conditions were really bad, I wouldn’t hesitate to park my aircraft where structures or vegetation provided some shelter from the prevailing wind. That Rotary Club toilet block might be just the thing. While people seem to always orient their aircraft to line up with the runway or hard stand, that’s not the bit that matters. What really matters is the prevailing wind direction. If you know there’s a blow coming from the south-west, then point your aircraft to the south-west. That will stop weather-cocking to an extent and reduce lateral forces.

Peg it Down

There is no one peg solution that will suit every need. I am a big fan of short, steel star-pickets and a large hammer, but that comes with a biggish weight penalty and getting them out can be fun. I also have some large heavy duty plastic tent pegs that are great for sandy areas. Those screw-in ones look really good, but require a ratchet socket or similar. I suspect that two different gauges of the screw in types with a socket driver would be the ultimate solution. Sometimes nothing works. On Horn Island I had to find some really large rocks after they parked me on an old section of hard stand that had concrete from WW2 under an inch of gravel. On Boigu Island I was banging in a steel picket while keeping a crocodile watch on the swamp beside me. I’ve seen people use logs of wood too in a pinch.

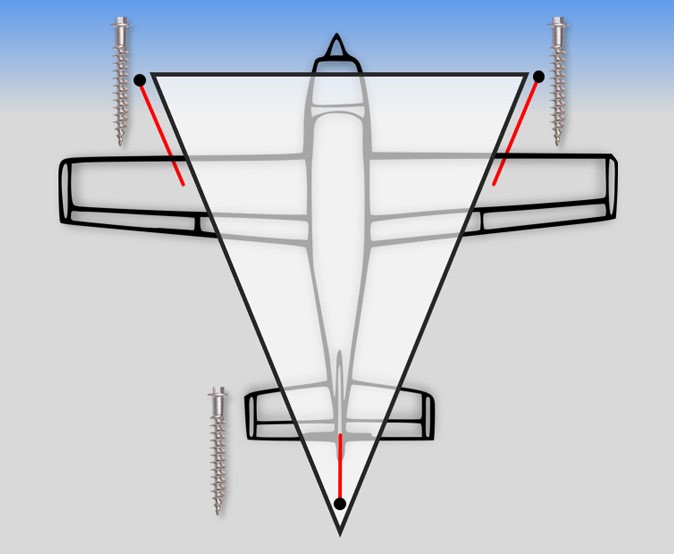

I like to deploy the underwing pegs about in line with the leading edge and slightly outboard of the tie down point and the tail peg about a meter behind the aircraft. That means the aircraft has resistance to left/right, back/forward forces, as well as up/down. In combination with a good set of checks on each wheel, I have confidence that the aircraft will be where I left it after blowy weather.

Locked and Loaded.

Aircraft movement isn’t the only potential for damage. High wind on control surfaces can cause them to flog and cause damage. Many aircraft have gust and control locks fitted for that reason. Some aircraft use the simple safety belt around the control technique. Make sure you deploy the recommended control and gust locks. In my book, every external lock should have a long, high-vis ribbon attached to ensure removal before flight.

In the rush to get going, having a walking-away-from-the-aircraft checklist is a good idea. If only to avoid the “have I left the iron on” moment.

For me, that list looks like this:

- Fuel off

- Master Off

- Locked

- Chocked

- Tagged (rudder lock & pitot cover)

- Tied Down

- SARtime cancelled

If that’s in place, you can walk away from the aircraft in good conscience. If the worst happened, you can put your hand on your heart and say “we did everything we could”. I bet your insurance company would be checking. If you hit a weather event like they had in Archerfield, Queensland in 2014, then all bets are off. What we prepare for are the everyday challenges. My co-pilots laugh at me, but I always take a picture of the aircraft as I leave it for the Insurance Company, if required. If you tie it down right, that’s not a conversation you will probably ever need to have. Fingers crossed.