On the 12th April 2015, it was a calm Melbourne spring morning as I quietly said goodbye to my family for “a few months,” bound for London. There was no fanfare — it was to be a personal journey — just me and my little amphibious Flying Boat, Southern Sun. She is a “Searey”, a two-seat single engine plane, that can land on runways or water, a modern plane built in the style of the old flying boats of the pre-war era. There are around 500 flying around the world, produced by the Progressive Aerodyne company in Florida, with most home built from their kit, but now available as a factory LSA (searey.com). Southern Sun was specially built for me by the owner of the company with this trip in mind.

I had spent the better part of 10 years researching the late 1930s Qantas Empire Imperial flying boat route from Sydney through to Southampton, England; via Asia, India, the Middle East and Europe. That was the Golden Age of flying, luxurious and romantic, I wished I could have done the trip back in 1938, but I was born 30 years too late. So I did the next best thing and planned to retrace the route in the Southern Sun which has 13 hours worth of fuel tanks built in, and up to 21 hours range in maximum ferry mode, utilising a large fuel bag on the passenger seat.

My planned route closely followed the 1930s cities, making changes mainly for political reasons; for example refuelling was once done on Lake Basra in Iraq, but permission to land there for this journey was denied. The path ended up being Melbourne — Sydney — Longreach — Karumba — Groote Eyelandt — Darwin — Timor — Indonesia — Singapore — Penang, Malaysia — Thailand — (Over Myanmar) — Bangladesh — Patna, Gwalior & Ahmedabad, India — Pakistan — Dubai — Abu Dhabi — Saudi Arabia — Aqaba, Jordan — Israel — Crete — Croatia — Italy — Marseille & St. Nazaire, France — Southampton & London, England.

The plan wasn’t just to fly the route, but to explore each of the cities on my journey. To seek out not just the landing spots of the old route, but the hotels where guests used to overnight on that romantic journey — 10 days from Sydney to London, staying at the world’s most luxurious hotels along the way. I would stay two or three days in each place exploring.

Having crossed Australia, landing at Darwin airport was my first ever operation at an international airport, and I was nervous. I had spent most of my years flying at uncontrolled fields and waterways, so mixing it with Boeings was all new to me, but something I was going to have to get used to. Where I could, I landed at secondary airports with international flight capabilities, but there were times, like at Dubai International, where I saw no less than 8 widebody passenger jets lining up waiting for me to land. I was also getting used to hearing “you’ll be number 2 to the Airbus.”

As nearly all of my flights were crossing international boundaries, I mostly needed to land at the major airports to clear customs and immigration. At Lake Como in Italy though, I was able to have customs/immigration meet me lake-side.

My first international landing was in Dili, Timor-Leste. The locals in Timor thought my little plane was kind of hilarious! They’d never seen such a small plane.

On crossing the equator between Indonesia and Singapore I was nerdily excited by my first equatorial crossing to see the GPS click over from S to N in the air. Then, as someone who had grown up sailing I turned back south to land on the ocean and taxi across the imaginary line as a boat. Buono!

But then I’d had this other idea and question gnawing away at me…

If the water goes down the sink clockwise in the northern hemisphere and anti-clockwise in Australia, what happens on the equator? So, I bought a plastic laundry tub and cut a drain hole in the centre bottom. Upon landing I took advantage of the Searey’s magnificent sliding window, leant out, filled my “sink” with water and lifted it up. Voila! No turning effect at all — the water just slowly went straight down. Thank goodness I never have to wonder about that again…

Flying around the tropics was tough work in a small slow plane, but I always flight planned with 3 hours spare fuel, which gave great peace of mind when flying around lots of afternoon weather systems.

I had planned to fly between 5 to 8 hours a day, with departures at 7am to try to avoid the worst of the afternoon daily rain. Being April I was at the tail end of the season. This cleared up as I passed over to the Indian region, but then we had some serious heat to deal with. By mid-morning the temperatures were regularly reaching the mid 30s and by lunchtime low 40s.

When I landed in Saudi Arabia I saw 53 degrees on my OAT (outside air temperature) — luckily I was descending at this point… But when I was at 100’ above the runway and ATC were surprised to see that “I wasn’t a helicopter” they made me do a go around and boy, did those temps skyrocket… As annoying as this was, it was also a godsend — it made me realise how hard it would be to take off with 12 hours of fuel in this heat. It occurred to me after a day or so, that the best thing to do was leave at 10pm at night when it was 20 degrees cooler. It was a long, lonely night flying over the desert, with just a few lights and stars to keep me company through the evening until I reached Aqaba, Jordan in the morning.

Once through the Middle East, a felt a huge sigh of relief…

The knowledge that Southern Sun uses the same Rotax 914 petrol engine in pusher mode as a Predator Drone certainly had me wondering about my sound signature, more than once nervously pondering “I wonder what call I make if someone starts shooting at me?”. From Dubai, to Saudi then Jordan, I then stopped in Israel for five days to visit Haifa, Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. My long-winded security clearance was generously arranged by Yigal from AOPA Israel.

Most of the paperwork for the trip was handled by a specialist agent in the UK, and while there was a year of planning in the paperwork, it all went smoothly. There was a plethora of paperwork at each port, usually requiring multiple rubber stamps and signatures, but I used ground handlers in each country which made this much easier. They were all very jovial and happy to see Southern Sun, and not once did I feel taken advantage of or asked to pay any cash on the side.

One of the greatest discoveries of my trip was the fabulous generosity of strangers. No matter where in the world I went, and how supposedly hostile our governments may have been toward each other, the people on the ground went out of their way to be helpful, giving up time and hospitality for the “perhaps crazy” guy who had turned up in this little plane that looks like a boat…

A stop at Lake Como was not part of the original flying boat route, they stopped in Brindisi and Rome in Italy, but how could I pass up the chance to land on Lake Como and visit the Aero Club di Como — Bellissimo! My wife flew in from Australia (commercially…) and met me there for a week-long break.

From here it was all getting close to the end and easier flying. While my entire trip was VFR, through Asia and the Middle East I had been controlled along airways like a commercial IFR flight, but from Italy onwards, once cleared from controlled airspace it was much like flying in the US or Australia. Finally, after crossing France and a quick splash’n’go on the Loire River, I departed for Southampton Water, where I had been given permission to do a touch and go on the water before proceeding to Southampton International to clear customs and immigration. Later that day I flew Some of the many incredible photos and memorable experiences from Michael’s trip. over the Thames and into Daymans Hall, a lovely grass airfield on the eastern outskirts of London. The flying club looked after me very well.

Well… there I was. Trip over. Wow, I made it. My wife had joined me again, and we had a few weeks’ break planned in the UK. I had to work out how to pack up the plane and send it home. After only a few days of discussion, with my quiet yearning to keep going, and my wife saying “you’ve been talking about a circumnavigation all your life, so why not keep going.” Oh, ok!

Having spent 10 years planning to fly to London, I now arranged to fly to the US. Southern Sun would follow the Flying Boat route where possible, from Southampton to Foynes, Ireland and Botwood, Canada en route to New York.

But range limitations would mean including Iceland and Greenland in the route! I really had a pretty good run with great weather over Greenland. I had some delays in Ireland due to low cloud, then a couple of hours at a few hundred feet over the ocean approaching Iceland to remain clear of cloud, but none of it scary. There was one incident involving fog and low cloud on the coast of Canada, that lasted only a few minutes, but did scare the living daylights out of me. Iceland and Greenland were spectacular beyond words, while Ireland is both the greenest and friendliest place on the planet.

After clearing customs and immigration in Bangor, Maine I jumped down the coast to New York, where I excitedly landed at Port Washington, Long Island, right where Pan Am and Imperial once landed having crossed the Atlantic. I “had” to fly the Hudson, and having seen the Statue of Liberty, Manhattan and flown over the aircraft carrier Intrepid, I dropped down for a water landing splash’n’go on the Hudson River. Gold!

After a few days in New York I planned for my longest leg of the trip so far — a non-stop flight from New York to the Searey aeroplane factory in Orlando, Florida. A magical flight, tracking coastal all the way, not only did I get to enjoy the myriad of coastal waterways but I heard the broad range of accents changing from North to South throughout the day — fascinating!

Annual maintenance and a few upgrades were made to the plane while at the factory, while I worked on plans to get back home to Australia. The route could not go via Hawaii due to range, so we would need to go up to Alaska, follow the Aleutians to Russia, then Japan, Philippines and Indonesia back to Australia. A long way around. All achievable, except Russian clearances were proving difficult. When I got to Seattle, I’d make a final decision — keep going, or pack the plane into a container and ship her home.

Having spent so much of my trip under the control of Air Traffic Control and following my expansive excel spreadsheet of destinations with set dates for clearances, the chance to fly across the US with only a loose plan was very enticing. I decided I was going to follow the entire length of the Mississippi; all the way from New Orleans up to its source at Lake Itaska. It was heaven.

But now I needed to get my skates on, for as I hear so many folks say these days, ‘Winter is coming’, and that’s no time to be in Alaska let alone out in the Aleutians… I did a mighty 12-hour non-stop flight from Minnesota to Washington, then the next day a short flight up to Seattle where I stayed a few days. Then I pushed on…

Jumping over Canada straight to Ketchikan, Alaska — then to Anchorage for a few days of final preparations. On leaving westwards for Cold Bay, I soon had to divert to Homer where I found a wall of cloud to the sea en route. My initial instinct was to fly along the cloud looking for a break, then I reminded myself that I really want to be at my sons 21st (he was 19 at the time) so I landed to wait for some clearer/safer flying. The next day it was lovely as I tracked to Cold Bay, where I then got stuck for 3 dreary days, before making the leap all the way to Adak. Where I spent the next 3 weeks!

There was plenty of nice weather in this time, but I was still waiting for Russian and Japanese permission. After a week it wasn’t looking good, so I had to come up with a plan B. What did I have to work with? Could I get straight to Japan? No, it would take 22 hours, at around 1800 miles, and I could only carry just on 21 hours of fuel.

But there was one option other than returning to the mainland and booking a shipping container…

Attu. The last of the Aleutian Islands. The most westerly point of the US. Not quite directly on the way, but if I could refuel at Attu, that would break the leg into a 6 hour and an 18 hour flight to get me to Japan.

But Attu is abandoned; no people, no power, no water, let alone fuel — just big rats and lots of them. Google Earth suggested the runway was still there and in OK condition. I decided I could ferry 6 hours of fuel in fuel cans, leave it by the runway, fly back to Adak, wait for the next weather window, then make one really big passage to Japan.

We flew out at dawn, with 6 fuel containers on the passenger seat and footwell, and 5.5 hours later arrived overhead a wet and rainy Attu.

I could see that 2/3 of the cross runway into the wind was usable, and the full length of the main runway was ok.

Despite there being no one to listen I made my radio calls, then landed, left the fuel in a small shed by the runway, disturbed lots of rats and took off again to make it back to Adak before sunset. So far so good.

A week later the weather was looking good again. The freezing level was down to 2500’, and with so much moisture in the air ice was forming quickly, so I decided to just stick at 1500’. The plan was to leave Adak during the day, arrive at Attu, refuel, then take off just before sunset and fly all night; in the dark for 15-16 hours and arrive into Japan in daylight, after 18 hours non stop and 23 hours flying for the day… what could go wrong?

Well, let’s just say I’m here today to write about it, so while it was a very tough flight, it all worked out ok.

I needed a few days rest once in Japan, and the weather continued to be difficult on the way home, but I made it to Japan in a week, then on to the Philippines over a few days then a pit-stop in Ambon, Indonesia before making it back to Australia. Feeling very pleased to be reunited with my family, and chuffed to have been aboard the Southern Sun — she had become the first Flying Boat and/or Amphibian to complete a solo circumnavigation.

Southern Sun, standing by.

Since completing his original journey, Michael has received widespread recognition, including being named Australian Geographic Adventurer of the Year. But his thirst for adventure didn’t stop there. In 2019, to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the first flight from London to Darwin, Michael retraced that historic route in his SeaBear L-72. This journey was not only a tribute to the pioneering aviators of the past but also a personal achievement, as he navigated the same challenging path a century later — using modern technology while honouring aviation history.

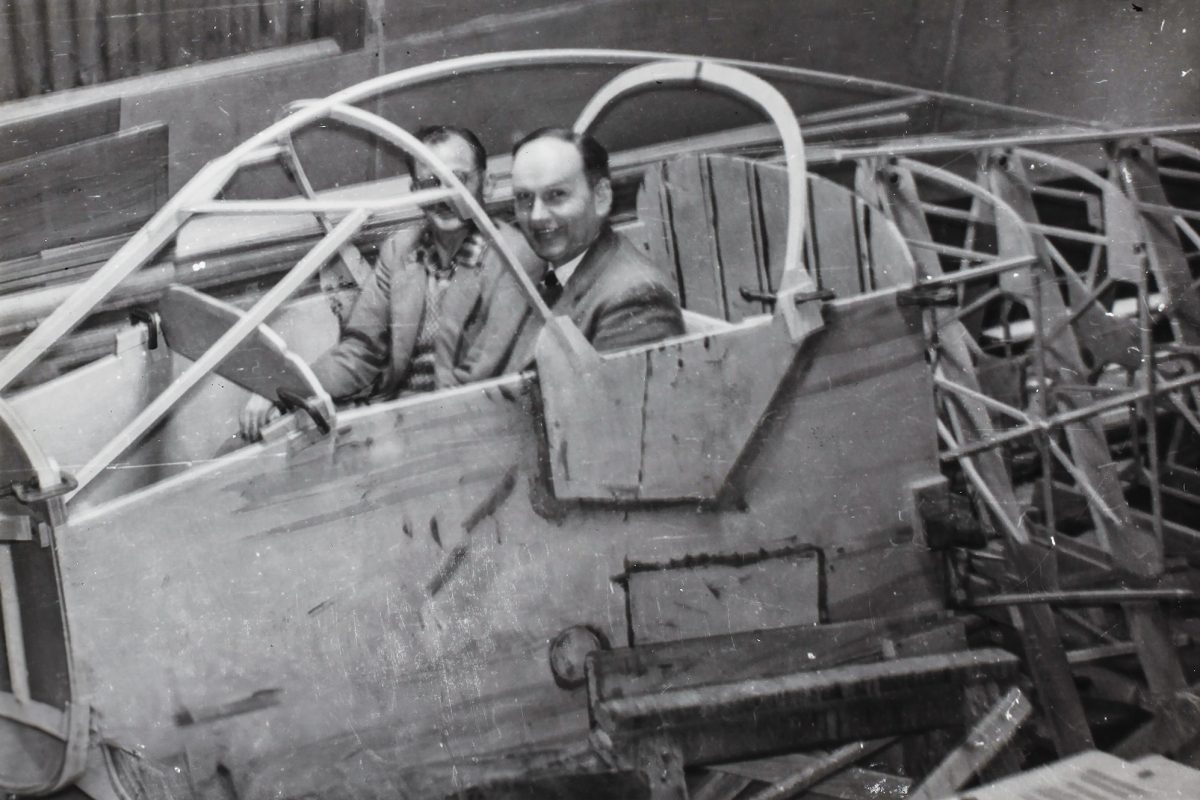

More recently, in April and May of 2024, Michael flew around Australia to mark another significant historical milestone — the centenary of the first aerial circumnavigation of the country in 1924. This pioneering journey, piloted by Wing Commander James Goble and Flight Lieutenant McIntyre, was conducted under the auspices of the Royal Australian Air Force in a Fairey Mk III D Seaplane. Michael set out from Point Cook and flew counterclockwise around Australia, completing the journey in 44 days with 27 stops. While he made every effort to follow the original route and timing, he did face his share of weather challenges altering his course slightly. One planned deviation, however, was to fly into the Gulf of Carpentaria, allowing him to take in the breathtaking coastline along the Queensland-Northern Territory border.

After speaking with Michael recently, it’s clear that he has a deep connection to aviation milestones, always seeking ways to honour them. With 2025 marking the 10-year anniversary of his original global journey, I asked if he had any plans to celebrate it. He responded saying, “I’m not sure yet, but I definitely want to do something. I’m still figuring out the details… Of course, what better way to celebrate than with another adventure!”

For those eager to learn more about Michael’s incredible circumnavigation, we highly recommend his book and documentary Voyage of the Southern Sun, where he provides a full account of the adventure available on his website.