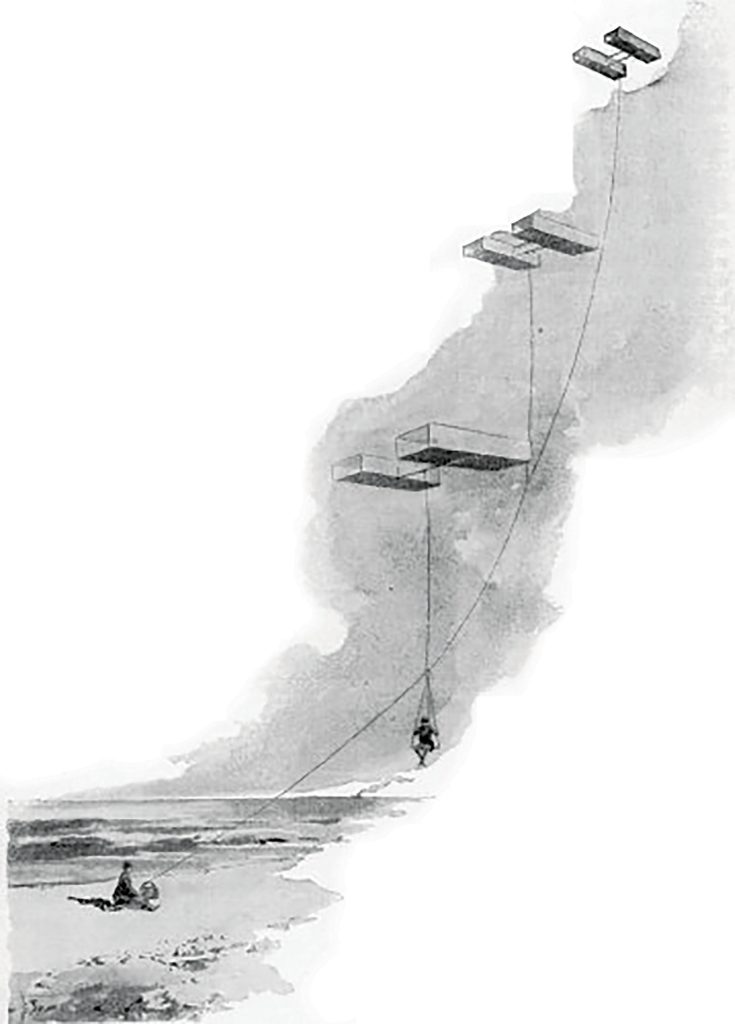

IT WAS QUITE A WINDY DAY AT STANWELL PARK, JUST SOUTH OF SYDNEY, ON THE 12TH OF NOVEMBER, 1894. WIND SPEEDS REACHED 21MPH (33.7KM/H), BUT IT DIDN’T STOP A CROWD FROM GATHERING IN THE IDYLLIC LITTLE VILLAGE. SCEPTICAL AS THEY WERE, THEY WERE ABOUT TO WITNESS ONE OF THE MOST IMPORTANT MOMENTS IN AVIATION HISTORY. AIDED BY A TRAIN OF FOUR BOX KITES OF HIS OWN DESIGN, LAWRENCE HARGRAVE LIFTED HIMSELF INTO THE SKY.

When you think about the birth of human flight, your mind likely takes you to Kitty Hawk, North Carolina with Orville and Wilbur Wright completing the first powered, heavier-than-air flight. Almost a decade before however, Lawrence Hargrave was looking down at those previously-sceptical crowds from 16 feet in the air. It was a momentous achievement, but just one in a life filled with groundbreaking experiments and inventions.

Lawrence Hargrave was born in Greenwich, England in 1850, son of the to-be Attorney-General of the New South Wales colony, John Fletcher Hargrave. When he was 15, Lawrence emigrated to Australia and two years later began an apprenticeship with the Australasian Steam Navigation Company in Sydney. For the next 10 years he sailed with the company as an engineer, particularly around the island of New Guinea on expeditionary teams. He later credited the experience as having a profound effect on his abilities as an inventor.

Returning to Sydney in 1877 and seeking a change, Lawrence joined the Royal Society of New South Wales, taking on a role as assistant astronomical observer at the Sydney Observatory. While he worked diligently in his time at the observatory, Lawrence left in 1883, determined to spend his life doing research work.

When John Fletcher Hargrave died in 1885, Lawrence inherited a considerable fortune, including his father’s property at Stanwell Park. While his father saw a beautiful seaside property, Lawrence saw an area with excellent wind conditions for aeronautical experiments. It was here he decided to base himself as he dedicated his time to inventing a flying machine.

In his time at Stanwell Park, Lawrence produced a number of important research results, theories and inventions that came to heavily influence aviation as we know it. Among his first major breakthroughs was his study of aerofoils. In 1892, Lawrence discovered that curved aerofoils, particularly those with a thicker leading edge, produced lift more efficiently than flat designs. While his later work never particularly made use of this discovery, it was quickly adopted by his contemporaries and is considered to be a founding step in the development of all modern aircraft.

Instead, Lawrence began working with kites, convinced that optimising the efficiency of a kite would help create a viable flying machine. In 1893 he developed a Box Kite, with two separated “cells”.

He found this design to have the greatest stability and soaring power, two key elements required for his ultimate goal.

By tying multiple box kites together in a chain, Lawrence was confident that he could generate enough lift to carry a human off the ground. If it worked, his invention would go a long way toward producing a viable overall aircraft design. If not… at least there’d be no chance of broken bones. And so, on the 12th of November 1894, Lawrence Hargrave set out to alter the course of aeronautics for the generations of designers to follow him.

It was a resounding success, one that provided a theoretical model from which countless European and American contemporaries based their aircraft designs. Notably, his work heavily influenced Alexander Graham Bell, whose tetrahedral kite designs were based off Hargrave’s own. In October 1906, aviation pioneer Alberto Santos-Dumont took off unassisted and flew for 60 metres in his “14-bis”, based on the Hargrave’s box-kite design. It was the first manned, powered flight publicly witnessed and filmed, and — thanks to its unassisted take-off — is considered by some to be the first true aeroplane.

Satisfied with his wing design, Lawrence turned to developing an engine that would work for aviation purposes. He developed one of the first rotary engines, driven by compressed air. Unfortunately, his design was heavily limited by the weight of materials and quality of machining available at the time. As a result, Lawrence was never able to produce his own independent flying machine. His work in the field culminated in an aircraft design published in 1902, one year before the Wright Flyer entered the history books, that never took form.

A keen inventor with an unbreakable resolve, Lawrence was never fazed by failures and setbacks. He was also an extremely modest man, who refused to ever patent his work. In an 1893 letter, Hargrave wrote:

Workers must root out the idea [that] by keeping the results of their labours to themselves[,] a fortune will be assured to them. Patent fees are much wasted money. The flying machine of the future will not be born fully fledged and capable of a flight for 1000 miles or so. Like everything else it must be evolved gradually. The first difficulty is to get a thing that will fly at all. When this is made, a full description should be published as an aid to others. Excellence of design and workmanship will always defy competition.

It was thanks to this incredible generosity that, while his work had laid a foundation on which modern aviation has developed, his work went largely unappreciated during his lifetime. In July 1915, Lawrence suffered from peritonitis as a result of an operation, and passed away aged 65. To this day, Lawrence Hargrave is hardly a household name, despite the impact his many inventions continue to have on everyday life.

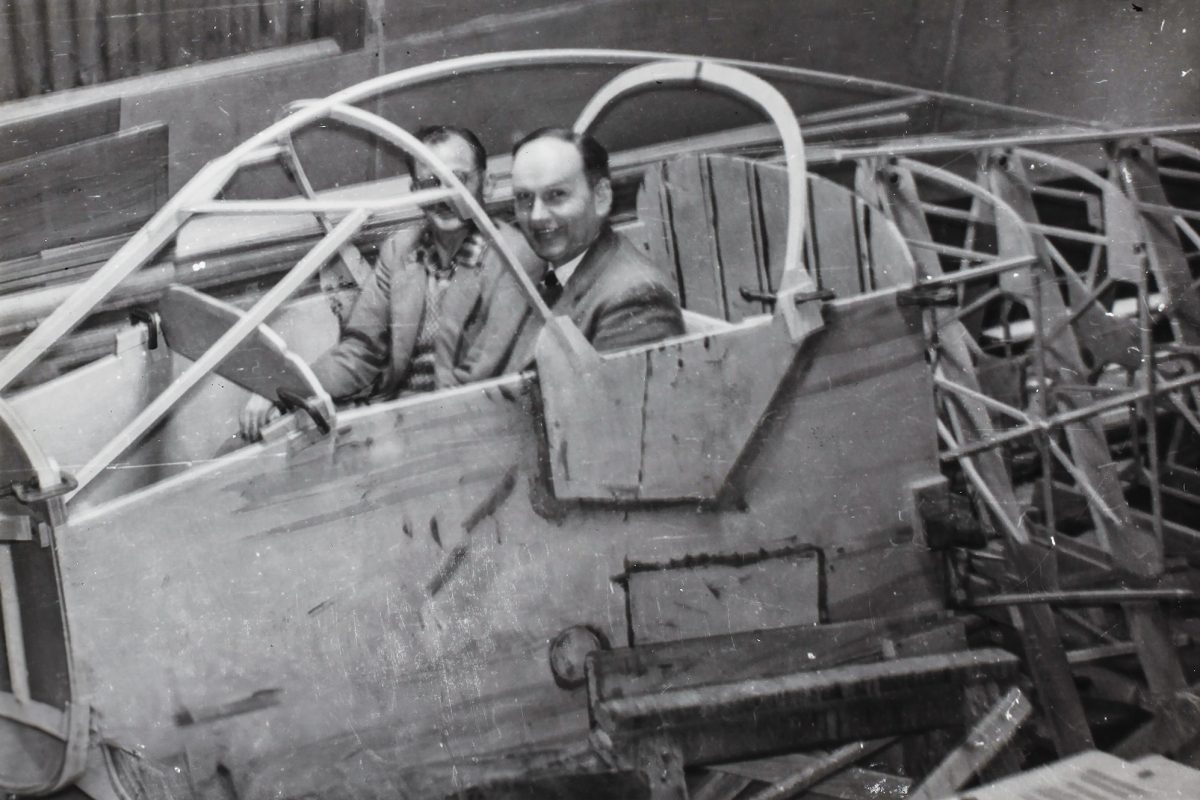

In 2002 – 100 years since his published design and 99 since Kitty Hawk – a group of students from the University of Sydney rebuilt Hargrave’s aircraft, replacing his too-heavy powerplant with a modern one.

It flew.