From a very young age I’ve looked after my possessions, and I was sure this would set me up well for owning and maintaining an aircraft one day. Standing in Tony Brand’s hangar watching the Horsham Aviation team hard at work on a fleet plane, I realised I’m further out of my depth than I’d thought.

Tony had me peering into a Cessna 150 engine bay – a soon-to-be ‘Group G’ contender – currently stripped of its cowling. “You see that?” says Tony, pointing to a bit of clear tube fitted to a strut. “Yes, but I don’t know what I’m looking at.” “Exactly”, he says, “because you’re looking at experience.”

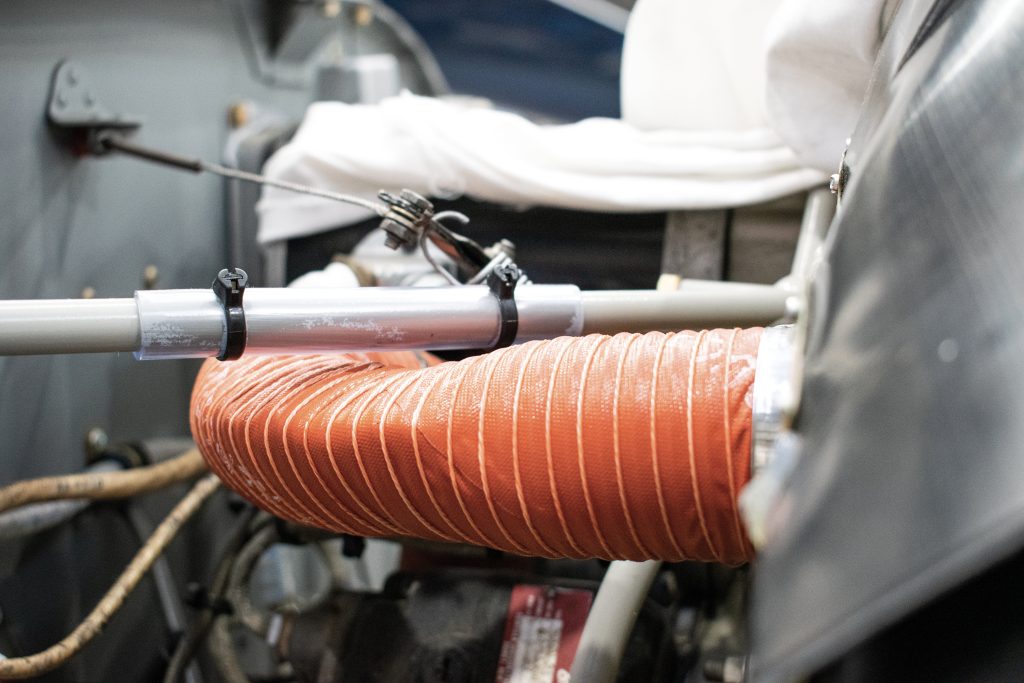

Tony had an entire wall stocked with folders, books, literature, various aircraft maintenance checklists and the like, all of which had clearly been put to use. But what he was showing me was critical preventative maintenance work that wasn’t in a book. There was a structural strut, under which an air duct/hose was fitted. “These tubes have wire rings inside them, and within a short period of time a shaky engine can create enough friction for one of those rings to wear right into the frame”.

There were two things that Tony had done as preventative maintenance. He’d wrapped the strut in clear plastic tubing – a cheap, replaceable ‘sacrificial anode’ for any friction – and he had re-shaped the air tubing into a flatter profile, creating more space between the tube and metal strut. “Any old John Smith won’t know to do things like this, you see, it takes someone who knows the aircraft and her tendencies, someone who’s seen progressive wear and tear over time.”

There were six people working on the same aircraft that day, all at once. One in the cockpit managing controls, three hunched over the engine bay, another two working on the control surfaces running various measurements and tests. Even still, they interrupted my chat with Tony to get a seventh pair of eyes to sign-off on their progress before they proceeded.

There I was, naively thinking that six workers would be tinkering with up to six different planes. I knew that the RAAus ‘L1 Maintenance’ didn’t cover a lot of the work they were undertaking, but it had me thinking – how could I ever replace this level of know-how on aircraft maintenance? I simply can’t.

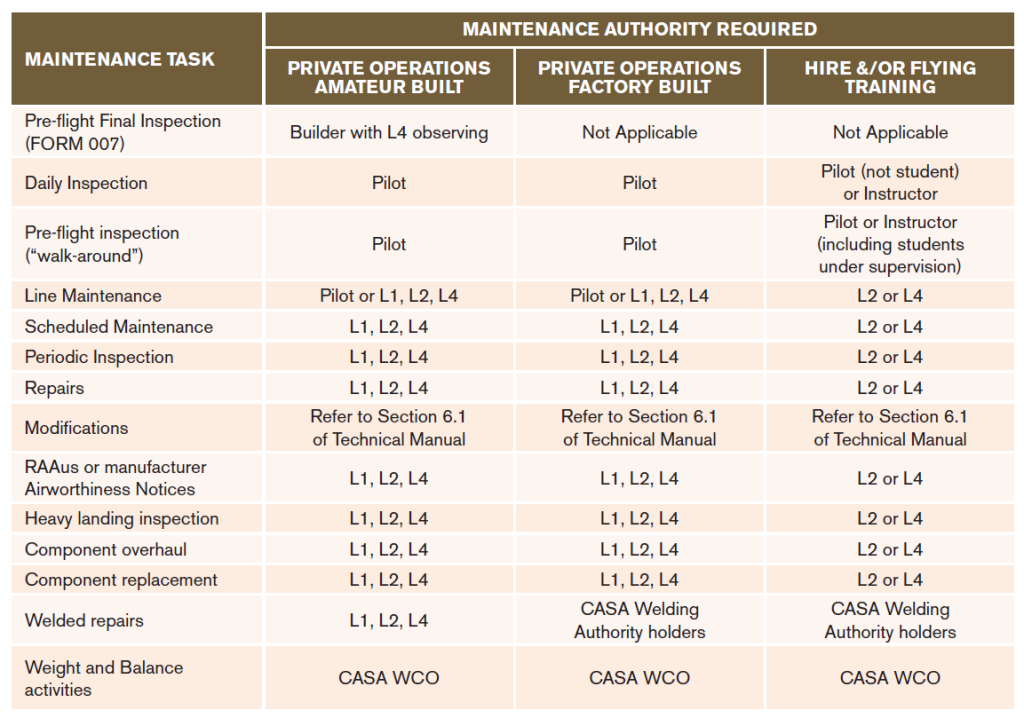

So, what can an RAAus pilot do by ‘default’, on the maintenance front? Well, there’s a list for that.

Most of what you see on here will be familiar, but I had to look up Line Maintenance to understand further. You’re automatically issued a Line Maintenance Authority as soon as you graduate from student to RPC holder.

From Section 12.7 of the RAAus Technical Manual Issue 41:

Provided it does not alter or require a change or disassembly of the primary structure of the aircraft, Line Maintenance is defined as:

- Removal or installation of landing gear tyres

- Repair of pneumatic tubes of landing gear tyres

- Servicing of landing gear wheel bearings

- Replacement of defective safety wiring or split pins

- Replacement of side windows

- Replacement of seats

- Repairs to upholstery or decorative furnishings inside the cockpit

- Replacement of seat belts or harnesses

- Replacement or repair of signs and markings

- Replacement of bulbs, reflectors, glasses, lenses and lights

- Replacement, cleaning, or setting gaps of, spark plugs

- Replacement of batteries

- Changing oil filters or air filters

- Changing or replenishing engine oil or fuel

- Lubrication of components

- Replenishment of hydraulic fluid

- Application of preservative or protective materials

- Removal or replacement of glider tow hooks

- Carrying out a duplicate inspection of a flight control system that has been assembled, adjusted, repaired, modified or replaced

- Carrying out a daily inspection on an aircraft

The truth is, I’ve been flying for over 10 years and I didn’t know I’m entitled to do half of these things – let alone knowing I’m doing them correctly with appropriate record keeping.

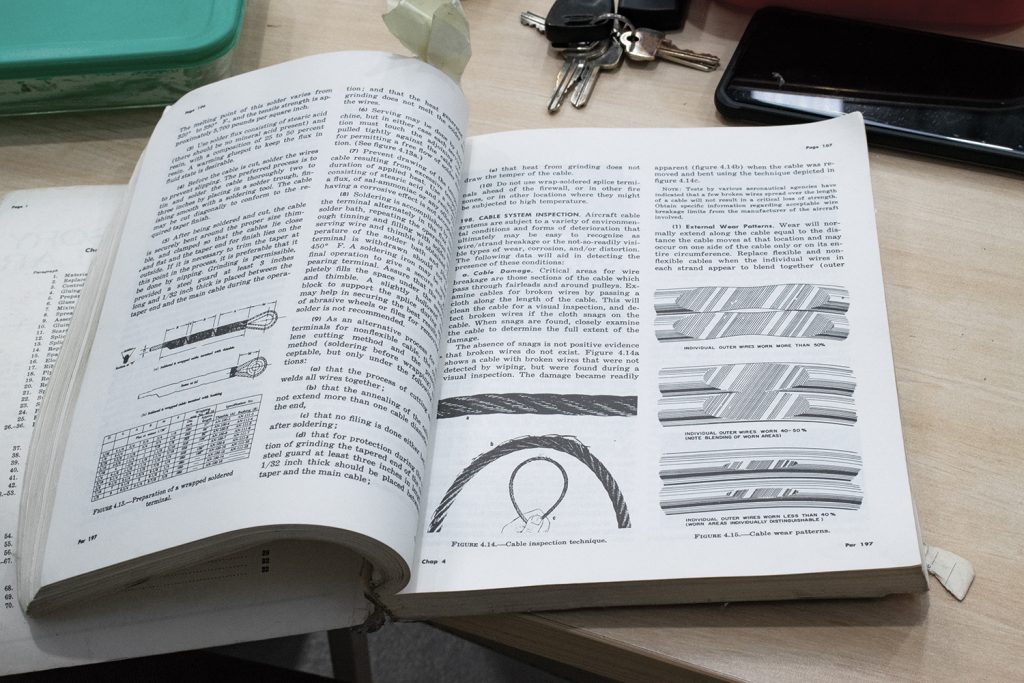

Over the years, I’ve almost flown a number of planes before making some pre-flight observations that I’ve logged in the maintenance release, or taken for further advice if I wasn’t comfortable to fly. These occasions taught me that one of my limitations is knowing the levels of acceptability. What makes for acceptable wear and tear on a cable, or a rivet, a weld, or aging materials? Where do you draw the line?

Tony suggested a very useful book, for just this: “AC 43.13-1B — Acceptable Methods, Techniques, and Practices — Aircraft Inspection and Repair” — you can access it online. It’s the bible of do’s and don’ts in Tony’s world. But that’s just a start, Tony had two more pieces of advice for me: Once you choose your aircraft, go and join the clubs and type groups that share the same aircraft, interest and maintenance — the pool of knowledge and experience is also something you won’t find in a book. Secondly, go and attend an L1 Maintenance Course: it’s fundamental for pilots.

I suspect it’s where all of us RAAus pilots should start, but unfortunately too many of us aren’t aware of it. Am I really capable of replacing or cleaning aviation spark plugs, beyond any doubt that I’ve done everything properly? I’d want someone qualified to show me that one, it’s simply a step-up from a lawnmower.

I started by picking up the phone and called Daz Barnfield at RAAus, Assistant Head of Airworthiness and Maintenance. He’s a LAME by trade and runs two-day courses around Australia for L1 Maintenance – and I’m booking in.

“The courses teach you everything from how to make correct and accurate log book entries, to understanding L1 limitations, where to find information for maintenance and how to use this information to make decisions around your aircraft and safe maintenance limits. You also roll the sleeves up and get a little bit practical with a few tasks, like changing an oil filter”.

Daz also mentioned there’s an L1 Line Maintenance course. “If you wish to maintain your own aircraft outside the Line Maintenance privileges, you can and need to complete the RAAus L1 owner maintainer course online via the members’ portal as well. We suggest they do the L1 Practical Maintenance course, when there is a course available.”

Sounds almost basic, right? Maybe, but not quite: a significant amount of the work that LAME’s have to undertake on a 100-hourly is simply preventative measures where there was little or no record of previous works undertaken – or inaccurate records, because the pilot didn’t know exactly what to enter. If it isn’t in the release, it didn’t happen. If it happens twice, it’s more expensive. The L1 course suddenly seems an obvious choice to me.

Tony was adamant that knowing the importance of compliance and following process means that nothing is left to chance. “Assumption is the mother of all problems”, he told me. And the father of all problems is get-there-itis. Between assuming everything is okay, and rushing the process, you’re setting yourself up for disaster. It’s often something a pilot didn’t see that became a problem. Taking your time with observations and maintenance checks is paramount.

With some L1 training under my belt, the appeal to me is partly tinkering in a shed, learning about the machine and enjoying that sense of owner’s pride.

The other part is more practical, keeping the plane running and maintaining the highest level of safety – maybe even saving on some costs, but for me that’s

an added bonus.

If cost-saving is the main driver for maintaining your own aircraft, let me pass on a few comments that have sunk in with me. There’s a big difference between an owner-maintainer and a LAME – let alone the six of them I saw working on the same aircraft. Don’t underestimate how much experience and training goes into aircraft maintenance above our L1 ticket. We also shouldn’t be maintaining begrudgingly: maintenance isn’t something that prevents us from flying, it’s what allows us to fly.

Many RAAus pilots don’t own their own plane, and as a result don’t consider themselves a maintainer. Tony’s start-up checklist was quite different to mine – he starts with the maintenance release. It’s usually the last thing I do, and it’s the first piece of his feedback that I am implementing. I almost felt stupid – how was I accurately running my pre-flight/daily inspections without looking at this first? It’s just what I had been trained to do – the maintenance release was the last step of the pre-flight. Not anymore.

I don’t know what I’d like to own, build or maintain yet – flying around and seeing or flying different aircraft is half the fun. I also know that I’m going to ensure I’m prepared, and that means sufficient training, knowing where resources are available and knowing how to use them. It also means, for me, I will likely choose an aircraft with a solid base of other owners and a reliable pool of information and resources. At the end of the day, my maintenance knowledge and decisions will be enhanced by all of it combined.