ADRIANNE FLEMING HAD AN AVIATION DREAM THAT SHE’D ALWAYS GRASPED ON TO TIGHTLY, EVEN WHEN SHE KNEW SHE WAS THE ‘ODD ONE OUT’ IN HER

ALL-GIRLS’ SCHOOL AS A CHILD. IT WAS THE VICTORIA POLICE’S AIR WING, FLYING LOW OVER ADRIANNE’S HEAD IN MELBOURNE, THAT WOULD INITIALLY DRAW HER HEART AND EYES TO THE SKY.

As I ask Adrianne Fleming to take me back to her beginnings, she laughs. “The beginning…”, she repeats it and chuckles. “It was climbing trees, trying to reach heights and get that bird’s-eye view. When the Police Air Wing units weren’t flying past, I was on my grandfather’s shoulders. I’d climb up on anything to get that view”, she says.

Adrianne dreamed of being on those police flights, behind the controls and soaring through the skies. “I felt like the only one – I thought ‘perhaps women don’t dream of being pilots in a similar way that most men might not want to be a childcare worker’”. At age 10, she finally experienced that view from the skies on a plane trip to visit her relatives – and Adrianne knew she wanted more.

For the meantime, Adrianne addressed her flight cravings with air shows and magazines. This was around the time that Deborah Lawrie (Deborah Wardley, whilst married) won a landmark sexual discrimination case against Ansett Airlines in the late 70s, becoming the first female commercial airline pilot in Australia. Reginald Ansett, himself, had said during the trial that he wasn’t discriminating against Deborah – but that she had the potential to fall pregnant, and he had a strong personal belief that women were not suited to be airline pilots. Here is a statement from the general manager of Ansett at the time: “Ansett has adopted a policy of only employing men as pilots. This does not mean that women cannot be good pilots, but we are concerned with the provision of the safest and most efficient air service possible. In this regard, we feel that an all-male pilot crew is safer than one in which the sexes are mixed.” Fortunately for Adrianne – and for women in general – Deborah won. She won Ansett’s appeal case, too. As a young girl, Adrianne had said to her mother “I want to be a pilot but what if they don’t let me?”. Her mother responded with a powerful response: “I’m sure the rules will change by then. But if not, we’ll fight them.”

Adrianne didn’t focus on the barriers that surrounded her, she focused on the dream. Finishing high school, Adrianne didn’t fill out her university preference card. There weren’t many university options back then, and she didn’t want to move to study in Sydney. Instead, Adrianne told her year 12 coordinator “I don’t want to go to university, I want to be a pilot” – at the time she was studying HSC maths, physics and chemistry – to which her coordinator responded, “You must mean you want to be an airline hostess?”. The all-girls’ school considered themselves as progressive.

Adrianne needed to find money to fund her air speed, but was without a full-time job. Her mother had an industrial relations role with the Melbourne’s Metropolitan Fire Brigade (MFB), which had an affirmative action program for female firefighters (they had none, at the time). “They measured your lung capacity with a chest measurement. It was ridiculous – if a woman qualified with the right measurement, she probably wasn’t going to be able to stand up”, Adrianne tells me. She attended Swinburne’s Associate Diploma in Fire Technology, trying to balance four days on and four days off to start her aviation journey. From an all-girls’ school to a male dominated environment, it was tough. Adrianne was even the test dummy for women’s uniforms.

Before officially joining, however, Adrianne completed the aptitude testing but took a Flight Data Officer position at Melbourne’s traffic control centre. Her fingers were crossed that it was her aviation entry point – that was 1988. Three of the 16 course attendees were women. Every attendee had a pilot licence – private, commercial… even instrument ratings – except for Adrianne. Adrianne just had a dream, and it was enough to make the cut. When her first pay check landed, she jumped straight into a cockpit for training.

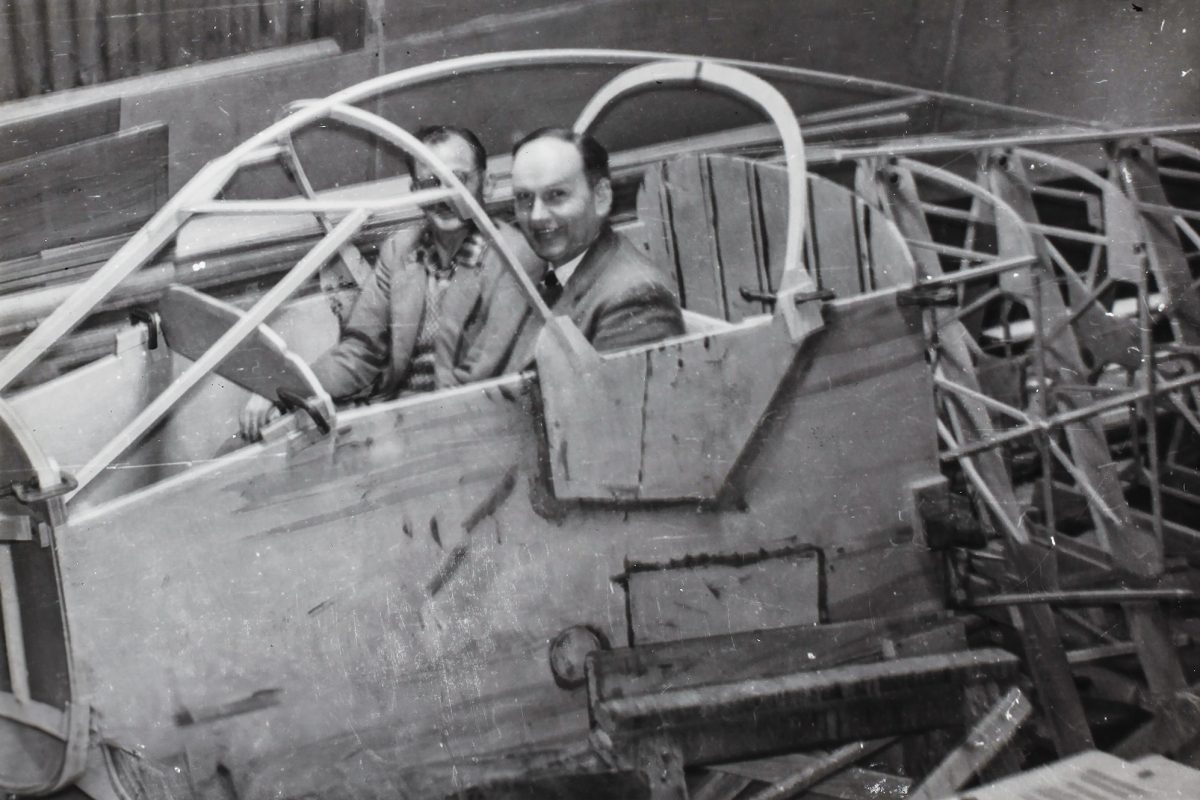

Three years old when her parents divorced, it was her stepfather and grandfather who were pivotal male influences. Her grandfather would pick her up from school, spend time with her and listen to her aspirational stories. “You’ll never know if you don’t try”, her grandfather would say. Her stepfather had a similar view – “You can give anything and everything a go”. Amongst all of this was an amazing husband, who was – and still is – devoted and supportive of Adrianne’s ambitions.

The focus was becoming a commercial pilot: “QANTAS is where I wanted to be”. The plan was to instruct, gain hours, then get into an airline. At the time, if you weren’t in an airline by 27 then you were told to basically forget it. They didn’t seem to recruit past that – there was a stigma associated with a 28-year-old aspirational pilot, that you’re essentially a failed pilot. Then, they were converting Data Officers to Air Traffic Control – with the same aptitude testers that worked for QANTAS. “If I became a failed pilot, then fine, but I’m going to find out either way”, Adrianne had thought to herself at the time.

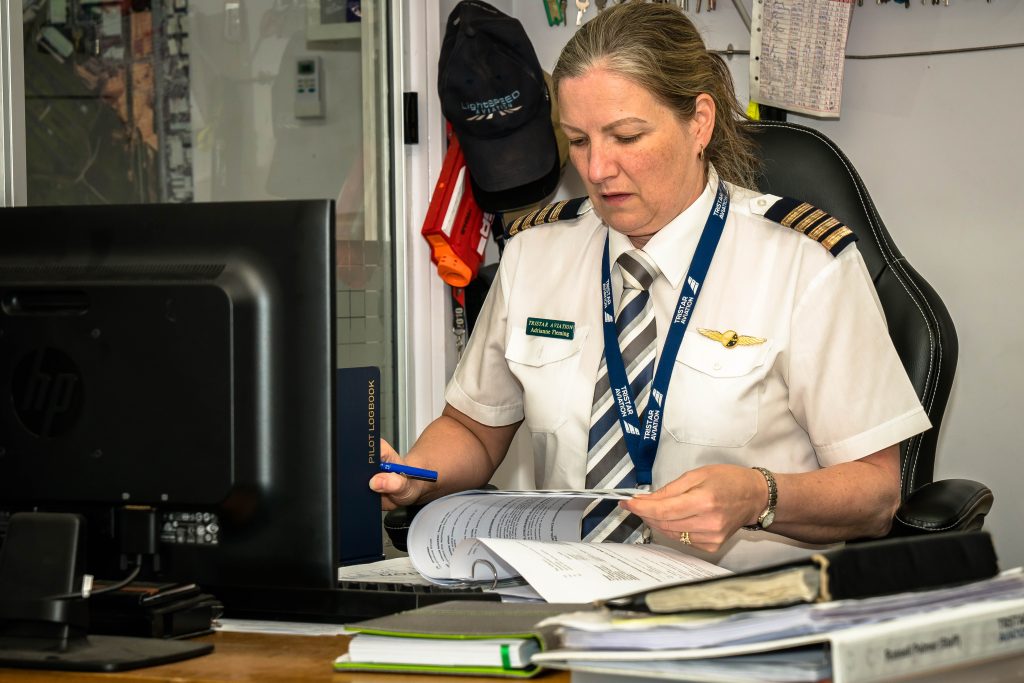

Adrianne had married another air traffic control officer, but it hadn’t worked out – they agreed on a divorce and remain as friends today. Times were changing in her career too, and she accepted a redundancy package. In the process, she even met her current husband – an instructor. He was looking to start a flying school, Tristar Aviation, now based out of Moorabbin, Victoria. They went on to start the school together, then had their first son. “Even starting the flying school, I was still thinking I’d be in a commercial airline – but after two years, I realised the school was where I wanted to be”, she said.

A little part of that dream kept niggling at her, and she was offered commercial airline jobs, but she never applied in the end – she kept following her feet. “I discovered how important my job was – first taught, best taught. And I realised that I now held the power to make other people’s dreams happen – what bigger responsibility could I ask for, than to deliver that?”.

Adrianne’s mum had bought her Nancy Bird Walton’s book, whom Adrianne later met and grew close to. Today, Adrianne has a photo of Nancy with her daughter on her desk and there have been many occasions where Adrianne has asked herself ‘what would Nancy do?’. She has always heard Nancy’s voice respond with ‘Out you go dear, get out there and do it’.

Joining the Australian Women Pilot’s Association, Adrianne became a State Vice President then President, before running a state conference within three or four years of joining. It introduced her to organisations, meetings, working with people and working with strong-minded women – some of whom initially petrified her. New working dynamics built a new confidence in Adrianne. She met Deborah Warden for the first time and realised she can achieve things, and the more she put in, the more she would get out. This led to different organisations and various roles or capacities, where she focused on pushing for change and progression.

Adrianne is currently opening up another Tristar Aviation wing in Launceston, Tasmania. “I was on a three-night trip, but with COVID it turned into four weeks so we used this time to renovate the space”. Adrianne also completed her RAAus instructor rating, which reminded her of days flying trikes and powered gliders many moons ago. Adrianne is a woman that enjoys learning new things. Adrianne and her husband started with a Cessna 150 for training many years ago – which she looks back on with fond memories for its reliability and familiarity. They now have a Tomahawk in Launceston and are looking at adding another.

When asked about her Order of Australia medal, Adrianne responded “It’s a medal of service, and it’s an unusual and humbling feeling to receive it – but I think most people who receive an OAM would share my reaction; ‘am I really worthy of something like this?’. It took me a while to accept and understand what it means”, she contemplated. “And what does it mean?”, I ask. “Well, you quickly find a lot of people attaching themselves to you, and not in a bad way – they were part of the journey, they identify with it and it’s as much an acknowledgement to them as it is to me. That is what helped me realise and understand that it isn’t a personal award, it’s a community award.”

Today, Adrianne dedicates her time to introducing people into aviation, and kick-starting their journey. She told me about an Air League Cadet that started training with her washing planes. He went off to study aeronautical engineering, continued to complete his PhD and started work in Area 51 doing secret things, now putting his PhD to work in government. She’s known him since the age of 14 (now in his 30s) and it’s countless journeys like his that Adrianne is focused on every day.

I asked Adrianne about her spare time. She mentions some craft hobbies like macrame, sewing, knitting and watercolour painting, but the conversation quickly returns to aviation. “I’ve been flying back and forth from India for 17 years. The school gets a lot of enquiries from overseas, too.” Adrianne has a book, The Left Seat, which talks about her journey and educates readers on how to start their own journey in aviation: what you need to know, what you need to ask, with tips about the system and the ropes and finding the right school and adventure for you. “I’m in the middle of translating this for India, with a plan to use the proceeds to fund women’s aviation scholarships.” At this point, I am wondering what Australia gives someone after they’ve already earnt an Order of Australia medal… is it a second one?

Adrianne also enjoys writing educational modules, as she refers to them – topics and areas that aren’t strictly taught in current aviation theory, but that are valuable topics in aviation – such as satellite navigation. Progressing this part of her journey is a five-year goal, she chuckles telling me it’s probably easier to implement such theory in India than jumping through the hoops of Australian requirements.

But she revels in other things – cooking a meal to spend time with her family brings the most enjoyment, with two sons and a daughter. All three have a relationship with aviation. Her eldest works as cabin crew for Virgin and Jetstar, her middle child is an apprentice aircraft engineer and her daughter is completing an Aviation VET course – close to getting her licence and even considering a commercial career.

And how could her children not be involved in aviation, in some shape or form, with a household like Adrianne’s? Whilst running the business, the most accessible holidays were joining the kids in a business fly-away. At that point, planes were just a method of transport… no different to a car, a train or a tram. They literally had arguments about wanting to go on a train or tram instead!

As I near the end of the conversation with Adrianne, I’m thankful for her time and broader aviation contributions. It’s reminiscent of the RAAus mantra ‘A pilot in every home’. There are a lot of moving parts in achieving that ambition, it all boils down to making aviation safe and accessible, plus a means of enabling aspiring pilots, which is where Adrianne has found her feet. Adrianne has been an apprentice to the likes of Nancy Bird Walton and Deborah Lawrie. She’s continued their work and footsteps to make aviation more accessible to others and she’s dedicated her career to learning the ropes so that she can show them to others.

Adrianne’s own footsteps have taken her on an incredible journey, and now she’s sending the next generations on their own ambitions. If you’ve learnt from Adrianne or have a story to tell, write into SportPilot at editor@sportpilot.net.au and let us know!